I didn’t plan to watch two movies about female war photojournalists in succession, but Hulu’s algorithm thought it might be a good idea.

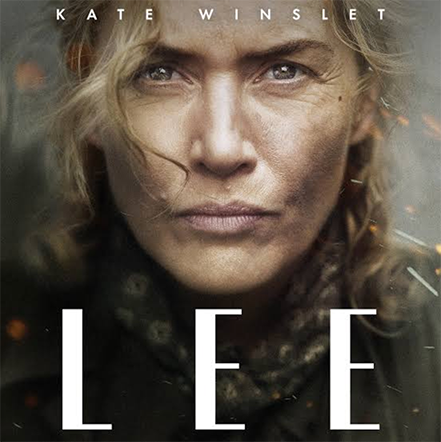

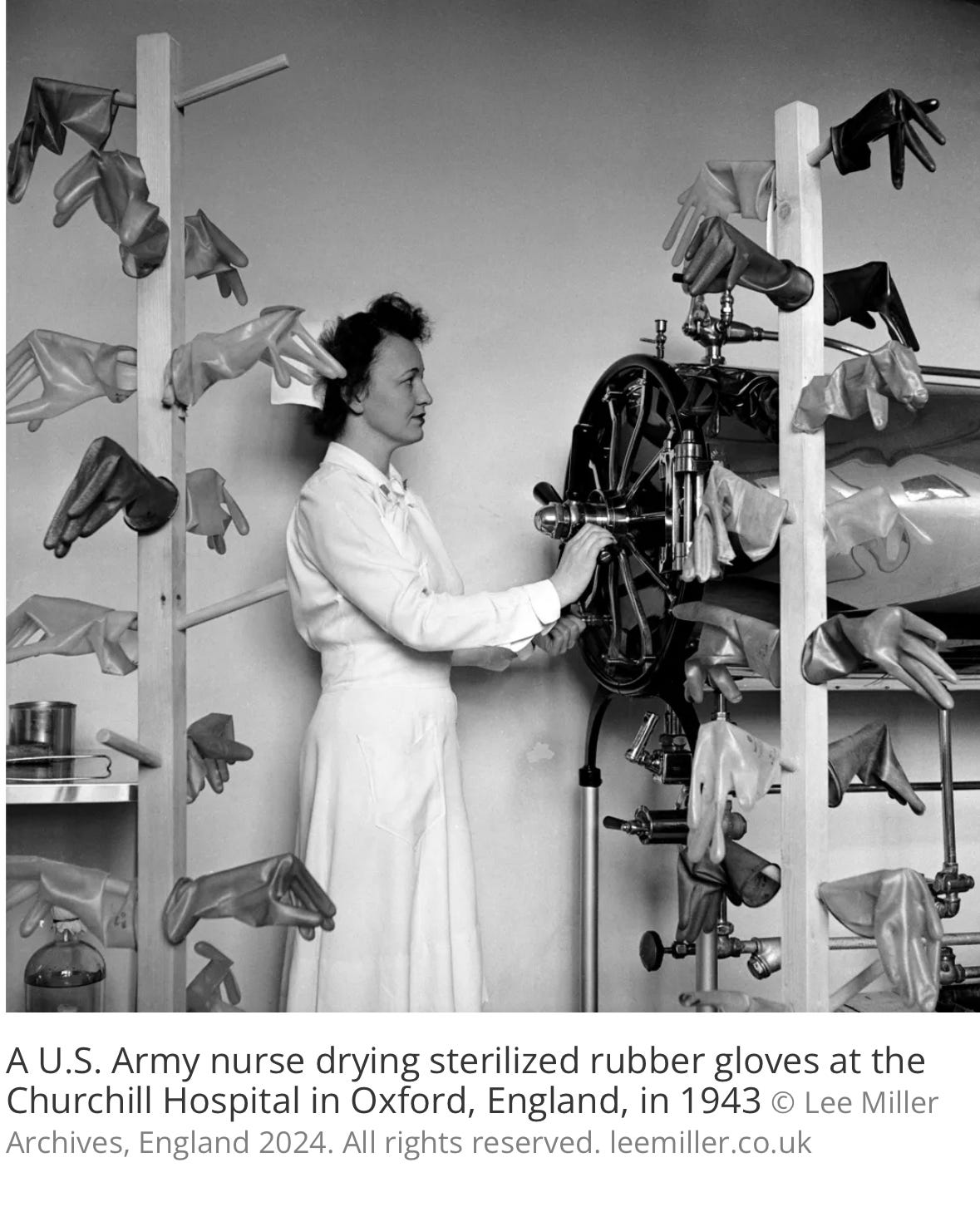

The first was ‘Lee’, the biography of a model turned war correspondent who was determined to tell the world the truth about the horrors of war. Kate Winslet was extraordinary in this role. When her young Lee sits in the French sunshine and says, “I was good at drinking, having sex and taking pictures, and I did all three as much as I could” in a rough, smoky voice, you know you’re dealing with a lady who does what she pleases.

When WWII began, Lee hoped to become a war correspondent, a goal that was previously unattainable for a woman. But thanks to her friendship with Life magazine photojournalist David Scherman (played by Andy Samberg) and her American citizenship she got a permit from the U.S. army that put her in the thick of it.

The film and her photographs show how intensely surreal life in a time of war can be. A sense of irony can allow someone who was as traumatized as Miller to survive these horrors and the memories they drudged up from her past with her sanity intact. Her intelligence and determination made this movie memorable.

Civil War’s photojournalist, Lee Smith, also has a goal – to interview the (future) President who appears to have started a second American Civil war. Kirsten Dunst did an excellent job with the role, but like everyone else in the movie, she is fighting, working hard, and taking great risks for little reward.

Neither side appears to have an ideology or a goal aside from getting a good shot or killing the guys on the other side. They say Near Future stories are actually about the present, and that’s true in this case. The movie is a strikingly accurate portrayal of our current Cold Civil war.

The politics were lame, but Civil War’s focus on photography was awesome. Lee Smith is hunting for the money shots with a standard, digital camera, but her young acolyte Jessie (Cailee Spaeny) uses a manual Nikon FE2 loaded with rolls of film. Very old school.

As a wedding photographer in the last century, I used a camera like that. Capturing images of people dancing in low light was immensely difficult. I have to give Jessie props for getting any shot that wasn’t a blur.

The movie also captures the sense of invulnerability you get while observing dangerous action through a camera lens. It’s a tunnel vision that propels you forward – you have a goal, the perfect shot, and nothing can get in your way. I was never a war photographer, but when I was blogging about terrorism, I would occasionally take pictures in the midst of civil unrest. Sometimes, I even planned it that way.

In December 2006 I visited Beirut when Hezbollah was occupying the city center and staging rallies in an effort to force the government March 14 majority bloc to give them more power.

I’d never visited Middle East before, but when the opportunity to go to Beirut was offered, I took it. I was curious about the complex politics there - and I also wanted to see the people I’d been writing about for years in the flesh.

Armed with my camera, I felt bold enough to walk up to people and ask to photograph them. They were usually happy to talk to a western journalist. As a woman, I probably seemed more approachable. Kids asked me to take their picture. It was fascinating and very surreal.

When I was in Beirut, I told people I was a writer and a photographer. I didn’t call myself a photojournalist because at that time, journalists were supposed to be objective. I was not. I had friends who were part of Hezbollah’s opposition, the Cedar Revolution. I sympathized with their goal of keeping Syria and Iran’s Hezbollah proxies from gaining too much power in the Lebanese government.

I felt so strongly about that goal that I was willing to put myself in a somewhat dangerous position just to get the truth out.

Although I was warned away from the areas controlled by Hezbollah, I did decide to wander into their downtown encampment. Unfortunately I decided to do this at night. The area under the overpass was filled with garbage and roaming dogs.The propaganda stands were neglected, Kalashnikov flags and hammer and sickle were both grey in the moonlight. A little kid, about 5 years old, was wandering alone, stumbling, apparently high or drunk. Older men sitting near the edges of curbs, a few groups of teenagers watched him and me with an expression that couldn’t be called sympathetic.

The atmosphere wasn’t like a Phish concert at night, it was more like the South Bronx, 1984. The shivers running down my spine told me to put my camera away, to refrain from wandering up to the tents to ask questions. I walked towards the street and stood in front of a bakery, looking for a taxi.

Another Beirut rule that applies to urban areas worldwide: When you’re not looking for a taxi, they’re always in your face – when you actually want one, they’re never around.

The baker was closing up shop, bringing in a cart of bread loaves. For some reason, he handed me a loaf of bread, and he refused to let me pay for it.

That sort of kindness was the “Beirut rule” that I saw in most of the neighborhoods I wandered through.

I was reminiscing about that while watching ‘Lee’. Americans were fighting for something during that war. Germany and Japan’s Axis was an existential threat to most of the countries on the planet. They could have destroyed our democracy and our way of life. The Cedar Revolution was also fighting an existential threat – occupation by hostile foreign forces.

But if present-day America did fall into Civil War, I would take great risks to avoid being any part of it. Both sides use journalism as propaganda, both disgust me to no end. I wouldn’t lift a finger to support or even document the actions of either one of them.

Both know what they hate, and they have no problem expressing their frenzied rage, but neither is fighting for anything.

The situation is so absurd, even surrealism fails to capture it.